What can we learn today from the tax incentive program that launched the biggest building boom in New York City's history?

We look back at another Gem from the Archives - a 1960 CHPC report evaluating the history of New York’s first tax incentive program for new housing construction.

In the aftermath of World War I, New York City was experiencing historically rapid population growth, driven by immigration and urbanization, coupled with a lack of construction. The result was an acute shortage of housing, with unaffordable rents, overcrowding, and other ills.

Today, the challenges the city faces are in many ways similar. Between 2010 and 2020, the city added more residents than in any decade since the 1920s. The supply of new housing has not kept up with increasing demand. Recent migrants have arrived in a city with record-high homelessness and a shelter system strained beyond its capacity, and already high rents have increased further.

In 1921, a special session of the State legislature authorized the City to enact through local law a temporary, emergency exemption from property taxes for residential property. This was the first such State intervention in New York City housing and tax policy. This tax exemption required “no awesome powers, no vast public expenditures,” but was highly effective in spurring new housing construction.

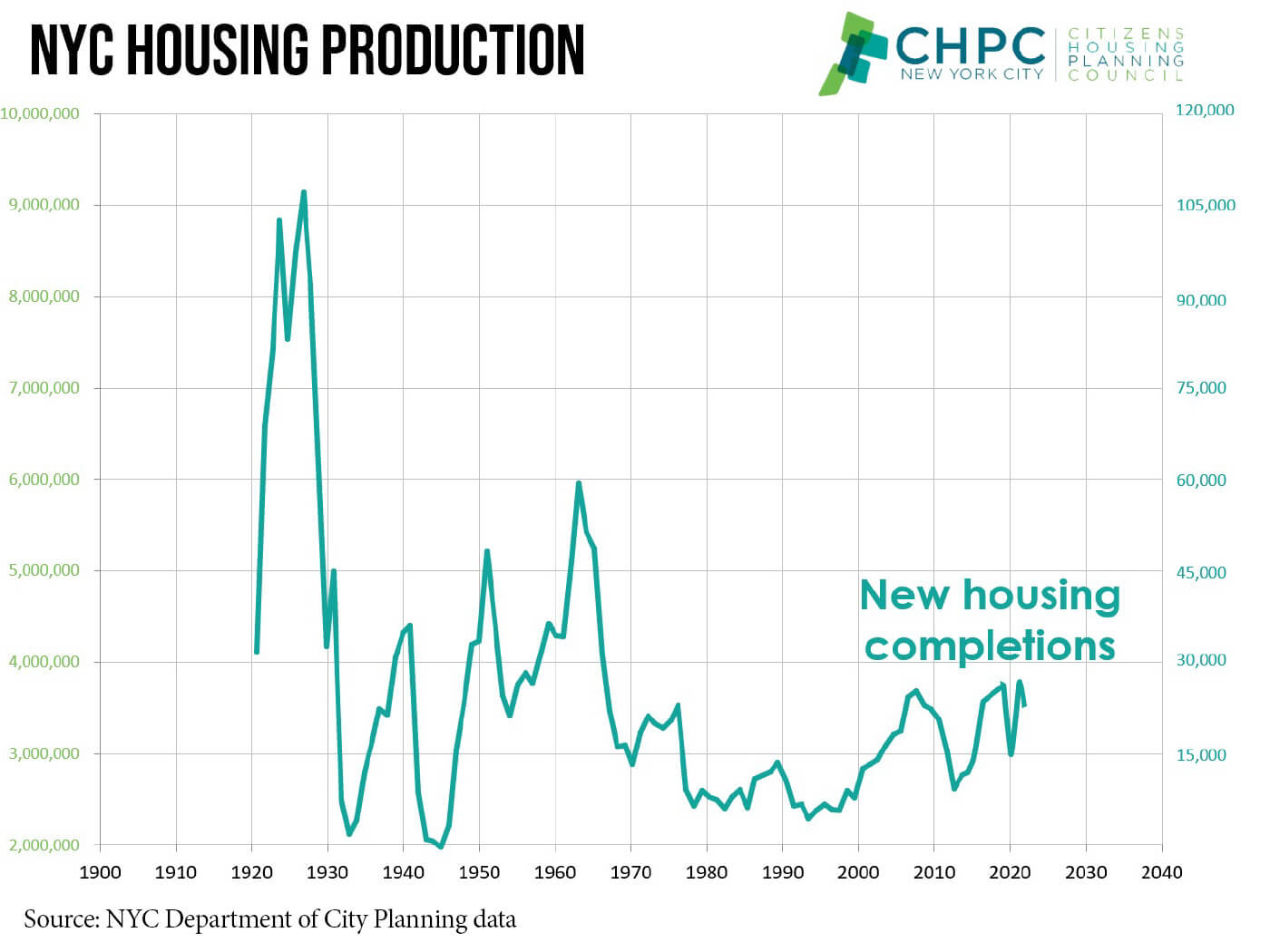

The housing boom that followed the 1921 tax incentive yielded more than twice the amount of housing NYC has built in any other decade.

This tax exemption, among other factors, made the early 1920s the period of the strongest housing production in the city’s history. More than 760,000 new units were built – more than twice what occurred in any other decade:

“The tax exemption law thawed the building freeze almost overnight. It attracted mortgage capital. It brought acres and acres of unused and underdeveloped land into use. … It ended the acute shortage of dwellings in three years.” (pp. 5-6).

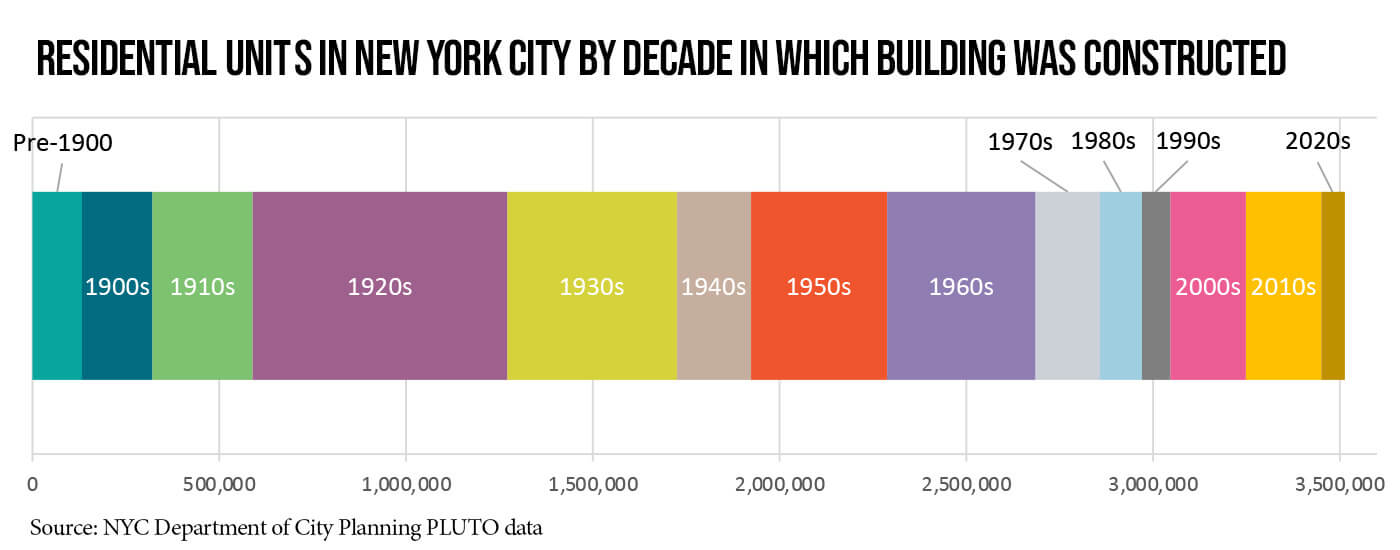

Beyond its immediate effects, this building boom has proven vital to New York City’s long-term housing needs. Fully 22% of today’s housing was built during the 1920s alone. That’s 50% more than exist from any other decade, and more than the amount built more recently than 1980!

While the jolt to housing construction stabilized the city’s housing market, neither this program nor others included provisions for affordable housing – the major investments and innovations that would make New York a leader in affordable housing still lay in the future. So this building boom did not produce new housing for those with the lowest incomes:

“There was, in 1920, a desperate need for housing of all kinds, and tax exemption provided housing in great quantities. Supply and demand appeared to have reached a near-normal ratio by 1925, largely as a result of tax exemption. However, the increased supply did not include adequate provision for low-income tenants. As this became more obvious, attempts to link tax exemption with some kind of control became more persistent. The crisis had been averted by the exemption, but the more permanent problem – the inability of private initiative to provide accommodations for those with low incomes – remained unsolved” (p. 23).

Following the experience of the emergency tax exemption, housing policy leaned away from supply-oriented solutions and toward the provision of low-cost housing specifically. The State Housing Law of 1926 shifted from incentives for private development toward a more robust role for government and limited-dividend corporations in slum clearance, with the use of eminent domain, in order to produce low-cost housing.

In 1960, the CHPC report observed that the turn away from supply-oriented policies toward targeted affordable housing provision following the 1920s housing boom had failed to eradicate the city’s housing crisis:

“[The account of the 1920s] does not always read like past history, because the problems of these years are our own problems. Money is still scarce; taxes are high; there is inefficiency in building activity causing high costs; low-cost housing is not produced in sufficient quantities. … The permanent policy embodied in the 1926 Law was not the answer, and no subsequent law or act has yet provided an adequate solution.”

Since this report was written, there have been many generations of State and City policies and programs, including the creation of many current programs to generate housing for low-income residents. One recent program, the 421-a tax exemption, began as a throwback to the policy arc traced during the 1920s. Created in 1971 to spur previously sluggish construction of multifamily housing, the program was amended many times in the ensuing years to focus increasingly on the production of affordable housing.

In recent years, the 421-a program played an outsized role in the production of multifamily housing. Of all buildings with four or more units completed between 2010-2020, the 421-a program accounted for two-thirds of all units, and 86% of all units that didn’t utilize a different tax exemption (such as 420-c or Article XI).

With this program’s lapse in 2022, and without the establishment of other programs to spur widespread construction of privately financed rental housing, the prospects are dim for the production of multifamily rental housing that isn’t already in construction.

Since the 1920s, we have built systems to provide housing affordable for people at lower incomes, while losing focus on the importance of increasing supply to overall affordability.

As a regional, national, and global economic center, New York City experiences a chronic undersupply of housing. To remedy this while delivering opportunity to people of all means and backgrounds requires a multi-pronged policy response, including measures to boost the overall supply of housing as well as significant investment in housing for lower-income residents.

In 2024, we look back at our 1960 look back at 1920, and we can see an arc traced by housing policy in New York: we have built systems to fill a critical gap left unserved by even robust market-driven construction – the need for housing affordable for people at lower incomes – while losing focus on the importance of increasing supply to achieve and sustain affordability overall.

To improve outcomes for New Yorkers, we need to learn from all this history. As before, money is scarce. Taxes are still high. Costs are still high. And low-cost housing is still not produced in sufficient quantities.

Historical housing production in NYC

The 1920s building boom that followed New York's first tax incentive program for new housing construction has not been matched since.

NYC housing by decade built

See the lasting legacy of the 1920s housing boom in the composition of New York City's housing stock today.

Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to documentation.

Featured Initiative

Featured Publications

CHPC's Marian Sameth and Ruth Dickler Archives and Library

Since 1937, CHPC has been at the forefront of every debate regarding legislation and policy that has shaped the physical environment of New York City and the housing market for New Yorkers. Due to this esteemed history, the Marian Sameth and Ruth Dickler Archives and Library offers invaluable, first-hand insight into the policy, legislation, and design decisions that created New York City today.