This week has witnessed a kerfuffle around Times Square. From complaints about topless women in the pedestrian plaza, concerns have now become existential for the plaza itself as Mayor Bill de Blasio has suggested it might be time to return the space to the use of cars. We dug into the CHPC archives to find out more about the pedestrianization of Times Square.

Of course, the removal of cars from Times Square is considered one of the more memorable urban planning achievements of de Blasios predecessor, Michael Bloomberg. But it was not the brainchild of Bloombergor anyone in his administration.

The CHPC archives hold materials that tell the story of the push for a pedestrian mall in Times Square in the mid-1970s. These include a pamphlet published by the Office of the Mayor (below) – who at the time was Abe Beameand its Office of Midtown Planning and Development.

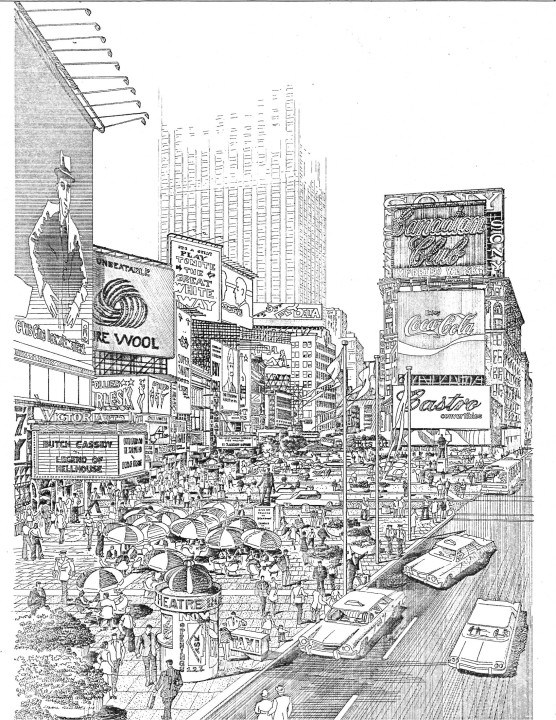

Broadway and Times Square have always been seen as places to stroll, it reads. In fact, as early as 1929 the Regional Plan Association proposed that Broadway be closed to traffic.

By 1974, Times Square had seen better days. The city in general was distracted with staving off bankruptcy amidst massive cuts to programs, staffing, and public services. As the executive director of the League of New York Theatres and Producers pleaded in a letter to Manhattan Community Board 5 members (below), revitalization of Times Square was overdue, with its attendant contribution to the deterioration of the area and its now worldwide poor reputation.

Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to documentation.

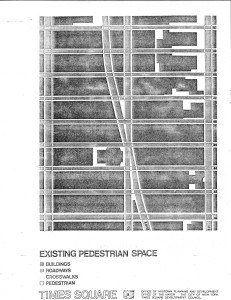

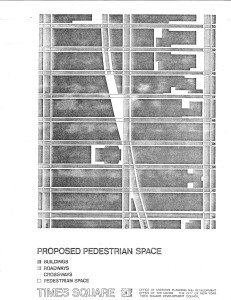

Reflecting the planning ethos of the time, the plan supported by the Beame administration did not go quite as far in closing the streets as todays pedestrian mall. Though Broadway was to be closed, Seventh Avenue was to remain openand taxis will be given special consideration in the plan. Still, expanding the islands of safety, from which pedestrians would dart through rushing traffic, into a full pedestrian plaza was a big idea at the time.

As The New York Times reported in 1975, not much progress was afoot (see below): For Times Square itself, the changes are symbolic. The great phase of office redevelopment ushered in during the John V. Lindsay Administrationbringing with it new theaters in office skyscrapershas closed.

Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to documentation.

Roughly 18 months later, the paper reported that the city government had won a half-million dollar grant from the federal government (below) to pilot the pedestrian mall. The permanent changes are contingent upon the citys being able to obtain nearly $4.8 million from the Federal Urban Mass Transportation Administration. That never happened.

Echoing many comments heard this week from New Yorkers and tourists alike, the Broadway Plaza plan says, The Broadway Plaza will be a beautiful oasis in the very heart of the city. Distinctive paving, benches, fountains, outdoor cafes, and festive banners will make Times Square a true stage for the city and mark the renaissance of the entertainment district.

So although aggressive or semi-nude panhandlers were not part of the equation in 1974, we can see that making Times Square a safe and enjoyable place was a priority for the city as far back as then and even earlier.

You can read the Broadway Plaza pamphlet here.

Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to documentation.